To this naïve viewer, there’s no proper introduction to the contradictory nature of Maurice Pialat’s cinema. Cahiers du Cinema’s suggestion that Pialat was a “marginal du center” (a pivotal, but marginal figure) of the post-New Wave era is a fitting, encapsulating description of the director’s career. The stubborn, late-blooming director was clear in his ambivalence for that particular movement, claiming in an interview with the Cahiers du Cinema that “the [New Wave] was all about a group of friends and when you weren’t part of it, you had trouble making films.” His first feature-length film wasn’t shot until near the end of the New Wave, by which point the movement’s most iconic filmmakers had already achieved international recognition. Pialat would never emulate those directors’ success, yet he was able to embody what the New Wave set out to prove: That cinema, as defined by filmmaker François Truffaut, would be “an act of love.” Linger on Pialat’s cinema long enough and it’s clear that he reached a form of universality that has remained unrivaled.

Pialat’s cinema is immersed in the lethargy of small-town suburban Paris, a crucial characteristic that deeply rooted the writer/director in French culture. As a child, Pialat’s family moved from the center of France — Auvergne — to the Parisian suburbs, creating a lifelong sympathy to the livelihood of the working-class: the shopkeepers, the cashiers, schoolteachers, the people of la France profonde–or, as he referred to, “the people who take the subway.” A stark overview of suburban inertia is tackled in his short, 1960 documentary L’amour Existe, where several of Pialat’s key motifs would be developed. The film’s opening line is a reference to the director’s first memory: “In a distant memory, a suburban train passes, as in a film.” The opening image is of people coming and going from the station; a high-angle shot of people moving up-and-down a stairway. It’s these images that prove to be the film’s foreword, grounding Pialat’s thematic association of the subway with the suburbs, a link found in the director’s later work. They situate the viewer (and by extension Pialat) in a definitive place and time that is uniquely separate from the urban environments of the New Wave.

Never an immaculate image-maker, Pialat’s camera compensated by portraying an absolutely brutal, austere look at the everyday. A lingering scene from L’amour Existe is a quick, simple shot of a lone child, seemingly lost or abandoned, crying out to no one in particular. Note that Pialat flocked to fictional cinema through documentary, making him distinctively qualified to portray that long sought after quality, truth. To even observe a camera movement on the first watch (or second, or even third), one would have to squint; Pialat’s camera moves along with the character(s), a subtle observer, never partaking in abrasive showmanship. That detached manner is purposeful, and even necessary, for his methodology. Although praised for his naturalism, Pialat rejected the term, instead insisting that what he did went “beyond reality.”

Grasping for a cinematic predecessor to his brand of filmmaking would mean looking back to the cinema’s infancy. Auguste and Louis Lumière’s actualités, oft-cited as a primitive form of today’s documentaries, remain (along with Jean Renoir and Marcel Carne) the only acknowledged influences on Pialat’s observant lens. Reflecting back on the shooting of L’enfance Nue, he would express that “…I was thinking about Repas de bébé,” in reference to the French title of the Lumiére’s Feeding the Baby (1895). The charming actualités captured a simple family dinner that was staged before the camera; the film’s reconstruction of an everyday event pre-dated any delineation between “fact” and “fiction” in a cinematic context. Lacking any established mode of formalism, the Lumiére’s work occupied a unique paradigm that Pialat found artistic inspiration.

Consider L’enfance Nue’s casting of non-actors and the connection to the Lumiére’s short becomes more apparent. The lost-youth film is given a new level of consideration and nuance in L’enfance Nue, a look at a damaged foster child, François, living in the suburban town of Lens. Pialat’s choice of a first-time actor to play the ten-year-old François (Michel Terrazon) is reflected in his decision to bring in strictly non-actors to fill out the rest of the cast. In an act of sincerity on the director’s part, the actor’s botched line-readings are kept as they are, suggesting an environment that allowed for the unexpected, the real. François’s foster parents are played by the nonprofessional couple Monsieur and Madame Thierry, who Pialat subsequently modeled their characters after. Although much of the character interpretation is fictionalized, subtle biographical detail is still interwoven seamlessly into the film’s scenario. Monsieur Thierry’s recounting of a World War Two story is, uniquely enough, the actor’s own poignant tale. This integration of biographical documentation with fiction is the very essence of a film by Maurice Pialat.

Later on, when Pialat returned to Lens to shoot Graduate First (1978) — about the limited opportunities provided for suburban high-school students — the lead actor’s everyday conversation was used as a basis for the script. Originally meant as a sequel to L’enfance Nue, Graduate First became a documentation of adrift, working-class youth, whose socioeconomic status had relegated them to a monotonous existence. Although tying him to the neorealism of year’s past, Pialat’s occupation with the cerebral rather than the psychological is what set him apart from his New Wave forebears. Socioeconomic status doesn’t drive the narrative of a Pialat film but is instead a byproduct of the director’s exacting capture of working-class life.

We Won’t Grow Old Together, a recounting of the frail relationship between a forty-year-old film director (Jean Yanne) and his younger lover (Marlene Jobert), is the closest Pialat ever got to pure autobiography. Instead of dictating the ups-and-downs of a relationship, Pialat decided to shoot an explosive “end-of-love” story, set around a cyclical series of volatile arguments and whirlwind reunions. The elliptical presentation of the film’s narrative is a common thread that would follow Pialat throughout his later work. Due to Pialat’s “weakness” (his own words) with creating a clear transition, many of the film’s scenes don’t connect spatially or temporally to what came before. What started out as a directorial defect soon became a stylistic flair, acknowledging that “time” in cinema is another act of artifice. Self-reflexive, yes, but never more than authentic. How else could he show his mother’s death by cancer in Mouth Agape with reverence to the scenario? In only eighty-seven minutes, the abstract nature of time is perfectly felt: death, as portrayed by Pialat, is both a slow-crawl and a quick conclusion, devoid of melodrama but profoundly sentimental.

Loulou and A Nos Amours are loosely adapted from the life of Pialat’s one-time partner and co-screenwriter, Arlette Langmann. Loulou, however, had a particular resonance for Pialat: it’s based on the breakup of Langmann’s relationship with Pialat over an affair she had with “Dede,” a member of Pialat’s production team. The film is told through the perspective of Langmann’s stand-in, Nelly (Isabelle Huppert), who, after leaving her bourgeois husband Andre (Guy Marchand), is brought into the company of Loulou (Gerard Depardieu), a charismatic lout with a minor criminal record. In Pialat’s hands, Loulou is anything but an unflattering expose on his ex-partner; instead, it’s an unsparingly honest and sympathetic menage-a-trois realistically performed to rare perfection. Behind-the-scenes drama assisted in crafting the film’s pugnacious naturalism. Depardieu, infuriated by the director’s psychological needling, fought back-and-forth with Pialat, who, according to Huppert, disappeared from the set for three days. Despite their combative rapport, Depardieu’s reaction to the final product was a rave: “I understood everything.” Even though Loulou represents the director’s romantic rival, it’s Depardieu’s character who is the most overwhelmingly sympathetic by the film’s conclusion. The actor’s natural charisma and robust facial-features act as a façade for the lonely drifter, who has come to the realization that he’s only loved for the sexual satisfaction he can provide. Loulou is arguably Langmann and Pialat’s most nuanced and fascinating character.

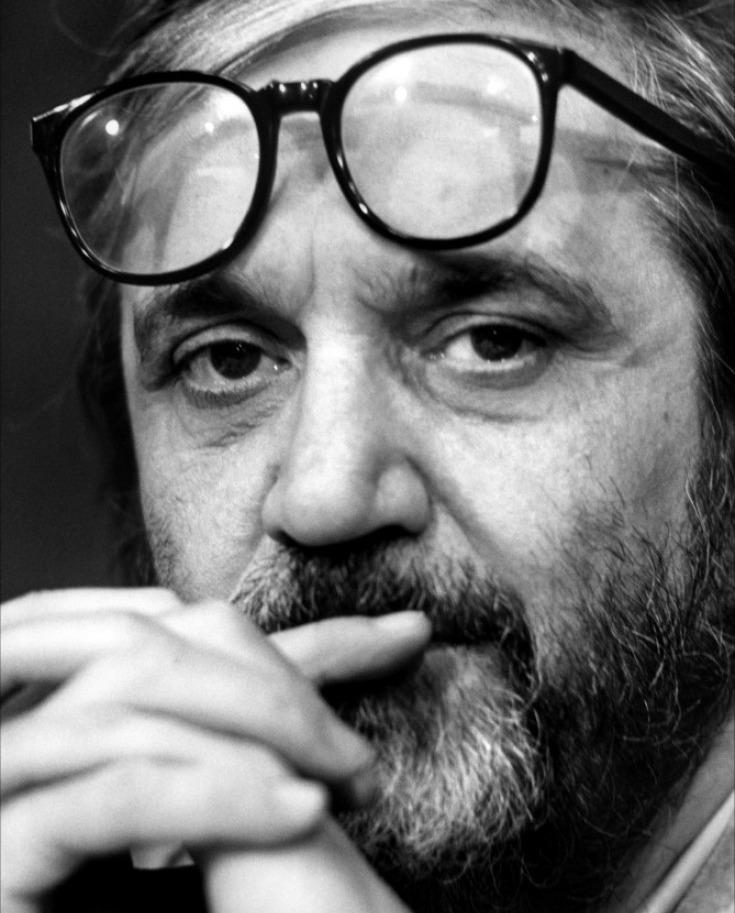

Pialat would return to the disillusioned youth in his follow-up, A Nos Amours, this time choosing to focus on a single character rather than a generation. Played by the magnetic first-time actress Sandrine Bonnaire, 15-year-old Suzanne is another character based on Langmann’s life. After experiencing her sexual awakening, Suzanne delves into a period of promiscuity, jumping from lover-to-lover in the hope of experiencing even a derisory amount of love. Her only true love is found in her overbearing but softhearted father, played by Maurice Pialat himself. A Nos Amours is Pialat’s first time playing a role in a movie he directed, casting himself when he couldn’t find anyone else to play the role. Arguably the sweetest (but never saccharine) moment in the director’s filmography is a short, inelegant tete-e-tete between Bonnaire and Pialat, about one of Suzanne’s missing dimples. The film’s artistic coup is the pairing of the youthful Bonnaire with the rugged, bear-like Pialat. The Bonnaire-Pialat combination is explosive, heart-wrenching, and most importantly, relatable on an emotional level. That is due to a mix of improvisation, a precisely scripted scenario, and a genuine relationship between the two. On set, Pialat became something of a father-figure to the burgeoning actor, and that chemistry is reflected in the final product.

Proving to audiences that he wasn’t solely confined to independent drama, Pialat took a turn toward genre — a cop thriller (Police, 1985), a literary adaptation (Sous le soleil de Satan, 1987), and a biopic (Van Gogh, 1991) — grounding each in a characteristically bleak verisimilitude. Depardieu, now Pialat’s go-to character actor, returned to play both Inspector Mangin in Police and Fr. Donnisan in the adaptation of Georges Bernanos’ Sous le soleil de Satan (Under the Sun of Satan), two films as similar as they are invariably different. Police is an observant study of a repulsive man — Depardieu’s inspector — and his attempt to unravel a Tunisian drug scheme. Although a wholly fictional character, the Inspector’s racist, misogynistic attitude is rooted in documentary material, gathered through the shadowing of undercover police by the film’s writer, Catherine Breillat. Where Police is prophetic and eerily stylish, Sous le soleil de Satan is secular and devoutly formalist. This Palme d’Or winning work is about a would-be saint’s struggle against both the literal and figurative incarnation of Satan, and the priest (Maurice Pialat) who has attempted to keep him leveled. Depardieu aside, the common denominator linking Police to Sous le soleil de Satan is Pialat’s ability to blend the fictional and the biographical. Bernanos’ novel pointed to a greater level of religious subtext, but Pialat’s adaptation is less concerned with subtextual critique than with the emotional immediacy of the character’s scenario. Fr. Donnisan’s one-on-one with Satan is treated with the same level of emotional intensity as one of Inspector Mangin’s interrogations, or even, a quiet moment of introspection by Van Gogh. Genre allowed Pialat to humanize those who are held on a pedestal of moral, spiritual, and artistic supremacy: an Inspector, a saint, and a famed painter are each as fallible, desperate, and lost as Francois, Loulou, or Suzanne.

Even though he’s often deemed the French Cassavetes and, sometimes, the French Ken Loach, Pialat’s work doesn’t contain either the anarchic energy of the former or the ideological drive of the latter. Really, there is no international equivalent to his unique place in the world cinema. Although Pialat’s work proved influential on the next generation of French filmmakers (and continues to, to this very day), his brazenly loose mise-en-scene has proven singular. Still, however, Pialat remained his own harshest critic, never recognizing his work as anything more than that of an amateur. The public’s conception of him as a belligerent enfant terrible didn’t help his reputation. He paid them no mind, and on the day that Sous le soleil de Satan won the Palme d’Or at the Canne Film Festival, a victorious Pialat spoke out to a crowd of applause and jeers:

“Today you give me the occasion to speak, and I shall be very brief. Here is my response. I should not fail to uphold my reputation. I am particularly pleased by all the protests and whistles directed at me this evening, and if you do not like me, I can say that I do not like you either.”

Forever an outsider.