“It’s not the job of films to nurse people. With what’s happening in the chemistry of love, I don’t want to be a nurse or a doctor, I just want to be an observer… I don’t think cinema is there to victimize or accuse people. Cinema has another aim.” —Claire Denis

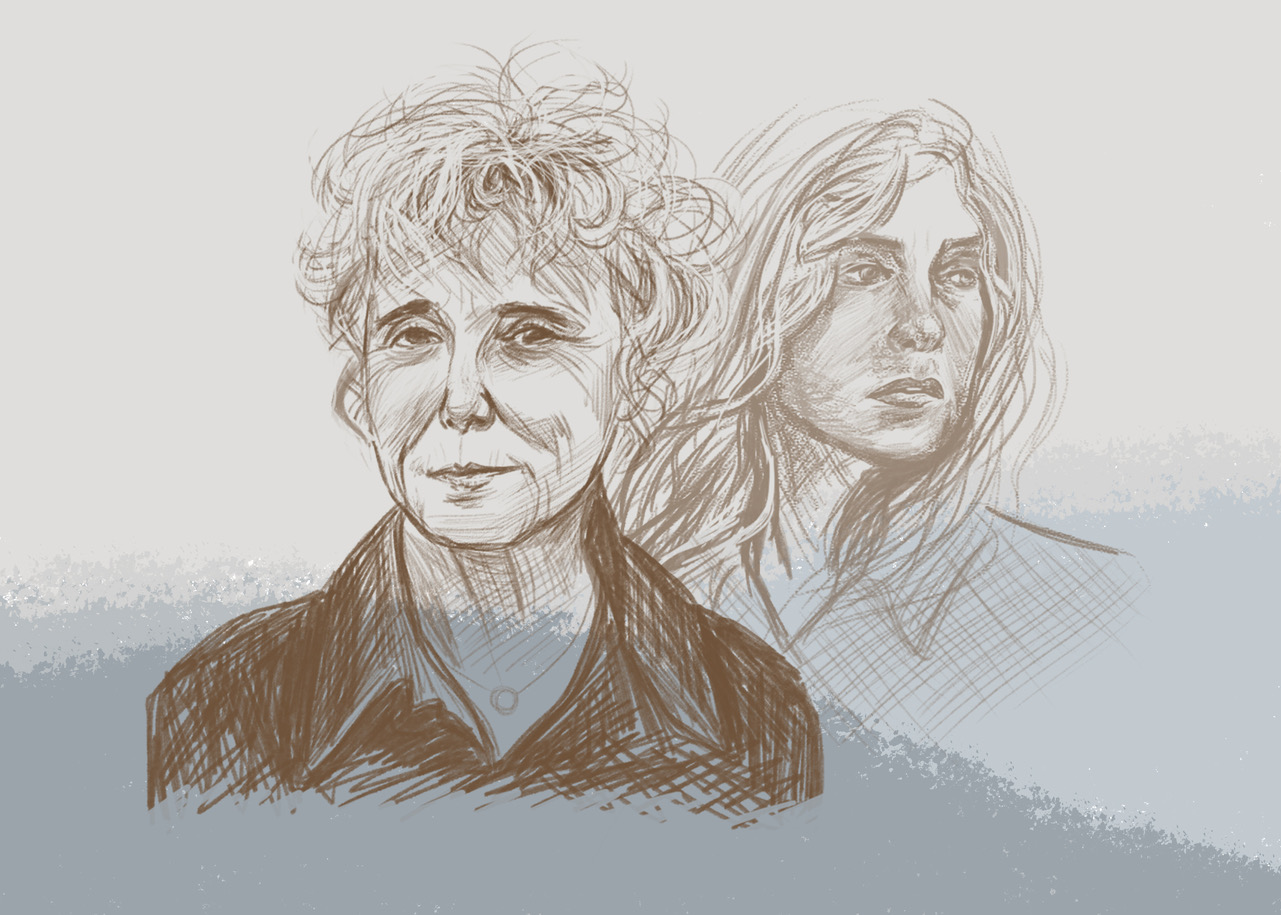

In the most challenging art, there is almost always an element of self-disclosure. For an artist to disrupt the status quo, to dispute a dominant ideology, or to “shake things up” in any legitimate capacity, they must lay themselves on the line, often bringing their perspective and background into the spotlight; first and foremost, artists must be honest to themselves. With her pensive gaze, meditative pacing, and distinctly feminist lens, it is hard to imagine a filmmaker better positioned than Claire Denis to evaluate contentious and controversial subject matter. Thus, it is no surprise that her 2009 French language film, White Material, is praised by both film critics and academics for its sensitive portrayal of a white coffee plantation owner, played by Isabelle Huppert, who finds herself caught in violent political turmoil as she tries to save her failing business. After all, Denis grew up in various French African colonies herself, and could be assumed to be well informed about this complex socio-political landscape.

Denis’ voice is indisputably valuable, but there are serious limits to her perspective that must be addressed, limits that the overwhelmingly white community of film academia has often failed to address altogether. While her struggles as a woman working in the deeply misogynistic film industry and her upbringing in the colonies aid in Denis’ telling of this story, the reality is that any white filmmaker will have gaps in their interpretation of struggles in postcolonial Africa. Denis is aware of these gaps and arguably uses them to serve her story, but it is important that we look at White Material with a critical and objective lens regardless of Denis’ caliber as an artist or her political intentions, evaluating the African representation on-screen. One must consider the risk of perpetuating Eurocentric power dynamics and perspectives by using the view of a white lead to portray a black community.

But first, a bit of theoretical background. When media is created under this hierarchy, it too is tainted by the dominant ideology of a given culture. Philosopher Louis Althusser described everything under the umbrella of media (film, in this case) as an “ideological state apparatus”—that is, an autonomous institution or pillar of society that is inevitably affected by the state’s ideology and power dynamics, even if inadvertently. Regardless of how “objective” a piece of media tries to be, it is ultimately subject to the same basic patterns of thinking as the society at large. This is where “representation” comes into play: whenever a reality is represented on screen, whether it be a specific historical moment or a community of people, the ideology of the state influences the representations.

Thus, when depicting a community—particularly, a marginalized community that has been oppressed and alienated by your community—one must proceed with caution. What gives Claire Denis the right to make a film about Africa, about blackness and whiteness? Can a non-black filmmaker even truly make a “black film”? How do we define black film? If it is a genre at all, it is a genre of genres, an amorphous, diffuse collection of highly varied films tied together by matters of authorship, appropriation, and cultural history. Black film could mean the idea of blackness being front and center thematically, or any film created by black authors. Really, by that definition, White Material is a “white film” made for white audiences, its very title referring to that elusive condition and artificially constructed notion of whiteness.

Indeed, in a literal sense, Claire Denis very much belongs to the community of colonizers. This cannot be denied. Her father, a white French geographer, traveled between several French occupied African colonies including Cameroon and Burkina-Faso, taking her along with him until she was fourteen. During this time, she observed various diverse communities, yet always through the lens of an outsider. The feeling of transient existence runs through all of her films; her works are almost always centered on outsiders who frequently encounter racial tensions in both France and Africa. Denis’ very first feature, Chocolat, is about an illicit romance between a white woman and a black man in colonial Cameroon. Beau Travail revolves around the French Foreign Legion’s occupation of the gulf of Djibouti. It is perhaps notable that her most frequent collaborator is Alex Descas, a black French actor whose characters almost always face injustice and oppression.

Born in 1946, I would argue that Denis still lived in the time of French colonialist rule, although most of her films revolve around the notion of postcolonialism. Postcolonialism, in itself, is a frustratingly slippery term. Traditionally, it refers to the demise of colonialism, and geographically speaking, it refers to those countries (most of which are in Africa) that were colonized and de-colonized. It functions as both an adjective and a concept. In white academia, postcolonial has all but replaced the phrase “Third World” as a less problematic and less demeaning alternative. But unlike Third World, postcolonial implies an awareness of the history of these countries, an awareness of the imperialism and oppression that caused their current economic crisis and poor living conditions. Unfortunately, the term postcolonial has problems of its own. The way it is used to describe all countries involved in colonialism effectively effaced the power dynamics between colonizer and colonized. Moreover, this term assumes that colonialism is over, blurring the chronology of independence movements and occupational rulings all over the world into one term.

Really, when academics refer to White Material as a postcolonial text, they say very little that is consequential or meaningful. The word evokes rebellion against colonial tendencies, a sort of reflection on the past, and yet, the term has been more commonly used to erase this history. White Material, though clearly opposing contemporary racial inequality and lingering white entitlement, reflects these vagaries of postcolonial academia. In fact, Denis’ film takes place in a generalized French speaking “Africa”; White Material’s setting is not a country, but rather, the idea of Africa. This massively diverse continent, separated into many countries with vastly disparate cultures and histories, is thereby reduced to one blur of colonial rule and poverty. One could speculate that this is Denis’ impression of Africa because of her frequent travelling from place to place, not to mention the fact that she lived in the countries so long ago. Perhaps this explains why White Material is defined by constant movement, constant displacement. In interviews, Denis has often said she shoots fast and edits slowly. This process results in films that are fragmented in a way that alienates many viewers. Her films are more like webs of information than linear progressions of events. Oftentimes, it will take multiple viewings to grasp the plot in full. In an interview with Cineaste, Denis offered some insight into her process, explaining that “For White Material, I broke the scene of the fire into two parts, at the beginning and end…I need some insecurity. It creates a sort of rhythm inside me.” Indeed, insecurity and uncertainty rule the reality laid out in the film.

Regardless of intention or influence, Denis’ flattening of culture and hierarchies into motifs is somewhat reductive. Her films could be described as hazy and fractured in terms of plot detail, but there is a tactile specificity to them as well, and this is one of the greatest strengths of White Material. Denis’ lens is obsessed with leathered skin, muscled bodies, mournful eyes, surfaces suffused with unspoken meaning. Hers is a cinema of the sensory, in which the immediate world supersedes all else and the air hums with sensual possibility. In White Material, Isabelle Huppert’s Maria radiates life, aching humanity constantly simmering under a placid surface, her expression hardly varying as her livelihood crumbles around her. Denis’ world is textured, tangible. But wouldn’t this raw, specific reality benefit from a more authentically established community? Wouldn’t a representation of a black community rooted in a specific time and place serve to create a stronger film?

If one wishes to evaluate whether White Material successfully deconstructs the ideology colonialism has perpetuated, one must first understand the way in which this ideology manifests. Colonialist media perpetuates racial biases via “othering”, in which foreign peoples or races are scrubbed of their individuality, consolidated into a mass of differences, and completely dehumanized. Othering allows traits and actions to be generalized, allows for racism to persist, and allows the oppressors to see individual suffering as an abstract concept. Othering is perhaps the most powerful weapon of the colonizing state; it is a means to transform ideology, to remove the humanity of outsiders and strip them of their rights, to trick the brain into perceiving these Others as lesser or lacking.

Does White Material participate in othering? At first glance, it seems that Denis’ film is part of the problem. In a film set in Africa, in a town populated by black Africans, very few black characters actually appear. There is the mayor, who seeks to buy Maria’s land from her by approaching her debt-ridden husband and manipulating his weakness and cowardice. There is also the rebellion leader, called “The Boxer”, whom Maria houses when she finds him on the run. Maria’s husband also has a son with his father’s housekeeper, a boy named Jose, who is half-African. These characters, who have few lines in the film aside from the mayor, are all essentially symbols. They represent the institutions and forces that bear down upon Maria—the patriarchy that prevents her from inheriting the plantation, the rebellion tearing this country apart, her husband’s alienating infidelity. They are, at the end of the day, symbolic roadblocks that keep her from happiness and security.

So, yes, on the surface, White Material actually does very little to subvert representation and French postcolonial ideology. Yet, looking at Denis’ history of intimate, subjective dramas, and not to mention her tendency to suggest without overt expository moments, is it possible that the world of the film reflects Maria’s limited worldview in order to critique this worldview? In the film, the decisions that Maria and her white family make based on their ideological assumptions always result in ruin. Maria’s son, Manuel, is so acutely removed from these “Others” that he can no longer see the real danger present in their lives and the degree to which these dangers could affect him. After being sexually assaulted by African rebels on his own property, he inserts himself into their conflict, believing his stolen shotgun and newly shaved head will prepare him to fight in this war, to take his land for his own. Ultimately, he is slain by the military who typically defend these white plantation owners, burnt to death in a house with the child soldiers he assembled to overtake the estate. Notably, he is fast asleep as he burns, comatose from drugs he has found in the house—even in death, he is separated from the pain of reality. Maria, on the other hand, assumes that her workers will stay with her during the conflict, that the mayor will not dare take her property, that the rebels will not endanger her family; she assumes that these conflicts are below her, that it is someone else’s war to be fought, distancing herself intellectually and emotionally until she is left with nothing.

However, in praising the film for its subversive and subtle interpretation of postcolonial angst and injustice, it is important to acknowledge my position. Like Denis, I am white, and I could never be the definitive voice in deciding whether this qualifies as positive representation and subversion of the ISA. While my Jewish heritage and American identity slightly remove me from the French colonial history that Denis is a part of, we are both outsiders. Denis has lived in African colonies, but her family was directly implicated in colonial rule and oppression. My family is rooted in an ethnic group that was historically oppressed and generally disengaged from French colonization efforts, yet I have never been to any African country or colony, much less lived there for much of my youth.

In many academic papers and reviews of the film, Denis has been praised for her uniquely “feminine” gaze, both in terms of empathy and in her ability to connect with the oppressed as someone who is excluded from the white male patriarchy. For instance: in the often frustrating paper “Postcolonialism in Claire Denis’s Chocolat and White Material,” Isabelle Le Corff writes, “Women have shared a history of oppression for centuries and have been consigned to the position of “Other,” being marginalized in the face of the dominant and departing from the Western patriarchal canon.” I quote her only because this explanation is a gross oversimplification of a complex web of privileges. To argue that Denis’ challenges as a female director are equivalent to centuries of colonial violence and destruction is a bizarre conflation of completely different power dynamics. I identify as Jewish, but does that mean I have indisputable authority on womens’ lives? Quite simply, arguing that Denis somehow has an inherent understanding and complete comprehension of black African oppression is inaccurate and misguided.

Empathy is a powerful tool, especially in the hands of a filmmaker as skilled as Claire Denis, and her ability to make the specific feel universal is a rare gift. Her fascination with reckoning differences shows up as a repeated theme in her films, and there is something to be said for the beauty of oppressed communities bridging their perspectives to foster connection. Perhaps Barry Jenkins, noted super-fan of Denis, put it best, explaining her approach in the simplest of terms: “I get the sense that she truly just doesn’t give a shit, that it doesn’t occur to her that she shouldn’t be ‘allowed’ to handle this material. It’s not a foreign world to her, in a way it might appear to be when you look at her and see a white Frenchwoman… [this is] someone who has not one question about what her rights are as a storyteller.”

Nonetheless, this bravery should not be confused with the ability to speak on behalf of these people who are often silenced or stifled in Western societies. White Material is practically a compendium of intersecting social issues, many of which are quite controversial to this day. Claire Denis is, if nothing else, a brave artist, a unique voice who shines a light into these messy clashes of class, gender, and race that do not often come with easy definitions, and certainly not easy solutions. This film does not provide a clean, easily digestible guide on positive representation, nor a lecture on the evils of ideological state apparatuses—yet as a piece of art, it is a beautifully stirring provocation that stings all the more because of its messy humanistic core. While it should be viewed through a critical and discerning lens, Denis’ singular work is valuable even in its imperfection.