“Memories and films are filled up with objects that we dread” – Maurice Pialat, L’amour Existe

Maurice Pialat’s A Nos Amours abandoned, and then consequently furthered, the tradition of neo-realism championed by Andre Bazin and the original Cahiers du cinéma—the notion that the cinema was meant to capture realism par excellence. Pialat’s work delved into the school of unkempt naturalism but never remained confined by any sense of neorealist objectivity. By harboring humanist regard for his character’s scenario, Pialat’s work has recently been embraced for its uncomfortable, squirmish verisimilitude. Rather than focus on narrative vis-a-vis documentary capture, Pialat’s pictorial expression, in his own words, went “beyond reality.” The director’s first work, L’enfance Nue (Naked Childhood), released near the end of the French New Wave (1968), a generation that Pialat actively felt distanced from due to their success (“They were succeeding, I was in the pits…”). And yet, in 1996, French director Arnaud Desplechin contested that “the filmmaker whose influence has been the strongest and most constant on the young French cinema isn’t Jean-Luc Godard but Maurice Pialat.” The director’s sui generis place in France’s cinematic historiography is one of contrasting ontological existence: a near balance and embrace of both misanthropy and humanism within the domestic sphere.

The opening of A Nos Amours is a medium close-up of 15-year-old Suzanne (a revelatory introduction to actress Sandrine Bonnaire) at summer camp, reciting a role in a romantic play by Alfred de Musset. Her face does not feign any overly romantic sentiment; it does not even seem she has a clear idea about how intimate love-laced dialogue should be delivered. A Nos Amour’s narrative structure is based around an oedipal search for love: Suzanne’s sexual awakening is followed by a period of promiscuity, in an attempt to seemingly retaliate against her overbearing, but adored father (played by Pialat himself), relentlessly demanding mother (Evelyne Ker), and pseudo-intellectual brother (Dominique Besnehard). Moving from partner-to-partner, Suzanne is incapable of feeling even a derisory amount of love for anyone but her father. Pialat’s use of a close-up on Bonnaire’s expression throughout is one of the cinema’s closest attempts at interpreting what can not be said in dialogue. Early in the film, Suzanne, and her boyfriend, Luc (Cyr Boitard), rendezvous outside the campground to make love, but her heart is not quite in it. They soon depart, her face recalling Buster Keaton’s stone-faced complexion. That same night she will impulsively hook-up with an American tourist, accepting that her love for Luc is not enough to consummate the relationship.

A motif of Pialat’s mise-en-scene throughout A Nos Amours is a tight, choking frame; a tense, overwhelming capture of Suzanne’s inner-experience. The film’s elliptical plot does not betray any straightforward understanding of Suzanne’s devoid emotional reaction. Several ensuing narrative episodes allow for insight into the emotional reality of Suzanne’s blank facade: that of the film’s core relationship between father and daughter. One night in direct violation of her father’s strict curfew Suzanne, her new boyfriend (supposedly unknown to either parent), and a small group of friends decide to go to a movie, pushing her father’s patience. In an act of impromptu acting, her father’s calm bear-like demeanor is instantly shattered, with Pialat (the actor) performing an unscripted slap to Bonnaire’s face. His response is a subtle nod to his knowing about Suzanne’s promiscuity: “stop treating me like some kind of an idiot.”

Much has been written about the director’s pugnacious style of directing; prone to quick-tempered arguments with actors; singularly demanding and psychologically exacting; a father-figure to the then 16-year-old Bonnaire; and put bluntly in Marja Warehime’s Maurice Pialat (the only English book-length study of Pialat), the director knowingly referred to himself as an emmerdeur (pain in the arse). For A Nos Amours, to go “beyond realism” meant directly translating Pialat’s authoritative presence on camera; through his on-screen presence, Pialat’s scene manipulation has taken on a new meaning, defined by a symbiotic pairing of director-actor-camera. Instead of simply augmenting his actor’s performance from behind the camera, he is now able to reflect his character’s emotional reality onto each scenario. Pialat’s slap does not deviate (or change) the scene as scripted but instead creates a layer of emotional violence that was not originally present. Bonnaire’s immediate facial and verbal response (“are you crazy?”) do not appear scripted, however, it is only our knowledge of Pialat’s improvisation that is directly influencing our perspective of the scene. Suffice to say, without that knowledge, there is not any cerebral way to discern whether or not an action was scripted, or another outgrowth of Pialat’s search for emotional exactitude.

As noted by Ken Jones in Filmcomment, Pialat’s style is a “mind-bending vitality of immediate experience trumps all belief systems, allegiances, plans.” That is to say his character’s emotional authenticity is of greater relevance to his methodology than any profound polemic moral. Any societal or political critique is then by nature a subtextual reading of his matter-of-fact capture of the domestic fold. But Pialat, however, is not working in heightened metaphor. While a subtextual reading of A Nos Amours would unearth a critical view of France’s post-WWII sexual imbalance and patriarchal oppression, neither is meant as an ideological drive to propel the narrative forward. Viewing A Nos Amours through that critically austere lense would simply strip away the film’s sense of spontaneity and humanism—in particular, the father-daughter

relationship. Assuming Pialat’s work is a harangue against the culture of la France Profonde, then Suzanne and her father’s connection would have to reflect some overt misanthropic perspective on the human condition. At the very least, Suzanne’s view of her father would be more one-sided, to more effectively highlight the film’s underlying social criticism. Pialat does not appear fascinated by such a completely sentimental view of family life, but rather, of presenting a cerebral and compassionate overview of emotional violence and undying love in equal measure.

Suzanne’s father is introduced about a half-hour into the narrative, by which point we’ve already witnessed her developing promiscuity; after sleeping with the American tourist, Suzanne’s briefly joined in bed by a school friend, who we will not see for the rest of the film. So far, structurally, the film’s narrative reproduction of Suzanne’s burgeoning sexuality is ambiguous to a fault. Pialat’s detached camera does not participate in any psychological probing, instead, viewing each scene through a pragmatic lens; emotional transparency on the part of Suzanne is only revealed through the director’s languid pacing, allowing the narrative to breathe and recontextualize itself throughout.

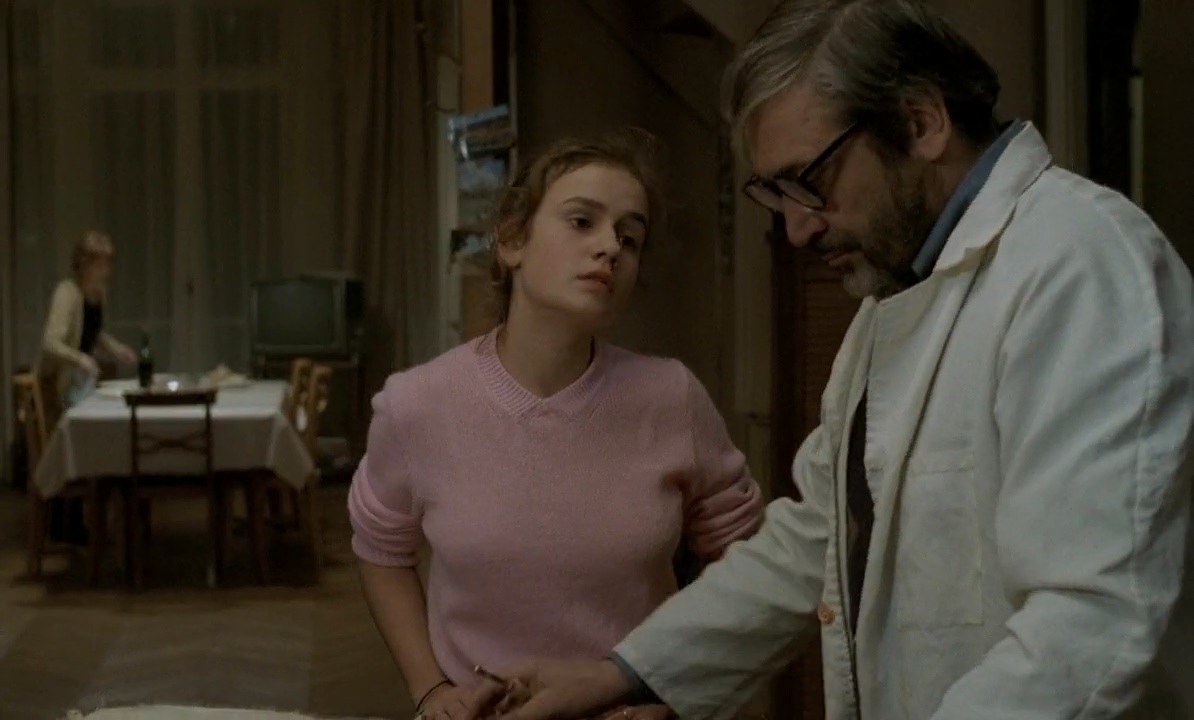

Consider the intimate scene between father and daughter that directly follows their previous argument. In one of A Nos Amours’ most touching moments, Suzanne and her father’s relationship is laid bare in a non-judgemental tete-a-tete. Key to the scene’s effectiveness is the actor’s maladroit handling of the candid material: they do not maintain eye contact, slouch, etc. Whenever Pialat’s characters try to act emotionally nue, naked, with each other, the result is an amalgamation of stilted segues, awkward dispositions, and softhearted tangents. This inelegant form of communication is a byproduct of the director’s search for situational honesty. How might one cinematically translate a visceral conversation between two people in a way that’s natural and truthful? Much of the scene’s impact is derived from how it is reframing the audience’s view of Suzanne’s jump from lover to lover. Suzanne’s promiscuity can no longer be categorized as something as cinematically orthodox as teenage rebellion, but rather, a teenager’s semi-philosophical ploy; one designed to recapture some semblance of her father’s love in the body of another. Pialat’s camera has the unique capability of magnifying the impact of such a spontaneous action into one of the film’s core moments of love.

Further, Pialat’s work in A Nos Amours does not attempt to moralize or rationalize human behavior. Later in the film, laying in bed with another lover, Suzanne offhandedly remarks how monotonous life is without loving anyone, continuing: “I adore my father, but that will not get me far.” A Nos Amours does not pass judgment on the father, even if it does not outright forgive him for his verbal scrutiny. That is because Pialat’s style is to only neutrally observe the coexistence of the father’s domineering influence and tender affection. Despite never superficially transposing the father’s inner torment into dialogue, the character’s exasperation can be felt in Pialat’s detached, straightforward demeanor. He is even direct with Suzanne about leaving her mother (and the family), the father’s apathetic facade stripping the scene of any overt sentimentality. Every motif of Pialat’s style up until this juncture can be examined through the father-daughter characterization in this one scene. An extraordinary spectrum of familial devotion interspersed with bitter resentment.

Pialat’s deft handling of the scene’s emotion is strengthened by the script’s relinquishing of any noticeable power structure. If the father’s physical abuse earlier signified the character’s dominance over the household, then this scene’s emphasis is on the back and forth shift of power between father and daughter; with the scenario’s cyclical nature being used to enliven the audience to the emotional tangibility of the scene over any didactic criticism. Suzanne is hurt about her father’s unexpected announcement of his departure but does not once allow him the moral high ground after learning of his infidelity (seemingly with a woman we never see or have referenced again). Much of what’s communicated is through subtext, Suzanne’s bitterness being conveyed through the dialogue’s fragmentary structure. Her father’s placid response (“why do you care”) is both oblivious and to a certain degree, regretful. No matter how close their relationship is, he cannot completely understand his daughter’s distance from him, his calm demeanor masking the brazen aggression behind his response. Yet, the moment’s drab melancholy is abruptly replaced by the film’s most glaring example of intimacy. Another tonal shift occurs when Suzanne’s father jokingly teases her about “a missing dimple” that he had never noticed before (not scripted). A Nos Amour’ s cyclical structure is a product of Pialat’s exploration of mankind’s foley; every affirmation of love is directly followed by an outburst of startling violence and vice-versa. The scene’s artifice is beholden to the director’s critical examination of human behavior. This manipulation of the “love-hate” pattern through a father-daughter relationship is an essential aspect of one of the film’s central themes: how can people exemplify hate but still find room to love? Pialat’s greatest accomplishment might then be his aptitude for visualizing each of his character’s point-of-view, lending A Nos Amours a clarity of character that is intimately revealing.

A Nos Amours is an alchemical combination of the cinema’s core elements, used to formulate a synthetic reality with a temperamental but genuine humanist core. The film’s imagery cannot be mistaken for maintaining a symbolic dimension, which would only avert attention from Pialat’s fascination with his characters’ volatile nature; the father’s domineering arrogance and contemplative benevolence; Suzanne’s credulous affection for her father, which is only matched only by her bitter-state; each character’s action and reaction a form of self-definition. The narrative cinema is not fit for “fact,” and Pialat’s exploration of realism does not mask his manipulation of the character’s blunt existence. It is this rumination on man’s equal capacity for brutality and tender devotion that formed a paradigm for those influenced by Pialat. Beauty in A Nos Amours is sparse, but even an action as simple as a conversation between father and daughter is a hard-won look at the best of humanity.