In the opening scene of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car, a screenwriter named Oto tells her husband the plot of her next script: a teenage girl sneaking into the house of a boy she likes. The girl enters the boy’s room, and she hears “an amplified silence, like the sound through a hearing aid.” The plaintive score cuts out when Oto says this, and only her low voice remains. This non-diegetic silence prefigures the meditative stillness that shapes much of the film. The unheard and the unspoken are transformed from gaps in communication to what Hamaguchi has called “another way of communicating.”

Drive My Car, the Oscar-winning film based on a short story by Haruki Murakami, is about the expanse of grief and all it entails—guilt, regret, and anger—and most interestingly, the obfuscation that can result from loss. The film explores how people try to make sense of their grief and the search for honesty when they have only their own answers. Hamaguchi and co-writer Takamasa Oe balance the ideas of truth and unknowability and our relationships to one another. It is fitting then, that language and communication are central themes. What characters say, and wish to say, is the emotional foundation of this resonant, sprawling film.

Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is an actor who stars as the title character in a multilingual production of the Anton Chekov play, Uncle Vanya. His wife, Oto (Reika Kirishima), is a screenwriter who devises her stories through a collaborative process with Yusuke—after having sex, Oto invents the plot of her stories. Her memory fades, however, and Yusuke must tell the story back to her the following morning. It is also revealed early that the couple lost a child twenty years ago, and this grief has become an undercurrent in their relationship that neither seems to want to confront. Oto has been having relationships with other men, and while Yusuke has known for a while, he resists bringing it up. When Oto asks to speak with him about a serious matter at the end of the workday, he bides his time, fearing the conversation could disrupt the precarious nature of their relationship. Yusuke eventually returns to their home to find his wife collapsed on the floor.

Two years after Oto’s death, Yusuke goes to Hiroshima to direct a production of Uncle Vanya. When he arrives, he is assigned a driver, who he sees as a barrier to his creative process. Yusuke prefers to drive his red Saab 900 himself so he can listen to his wife’s recording of the play that contains intervals for him to recite Uncle Vanya’s lines. But he gradually forms a friendship with his driver, a reticent young woman named Misaki (Tōko Miura). While this relationship is developing, Yusuke also deals with the presence of Takatsuki (Masaki Okada), the man Oto cheated on him with before her death and whom he has cast as Uncle Vanya.

The film is intertextual, moving from play rehearsals to real life, and lines from Uncle Vanya are as important to understanding the characters as is their actual dialogue. Yusuke seeks an exact rhythm to his staging, which befuddles his cast at times. When one actor asks for a more direct explanation of how to improve, Yusuke says, “You don’t have to do better. Just read the text.” He wants to replicate the pattern of Oto’s recording, the perfect spacing of dialogue that makes each word lodge itself into a neat order. Unlike real conversation, which is privy to hesitations and stutters, the text is full of certainty. Yusuke regards the text as a repository for one’s inner self: he says at one point, “Chekhov is terrifying. when you say his lines, it drags out the real you.”

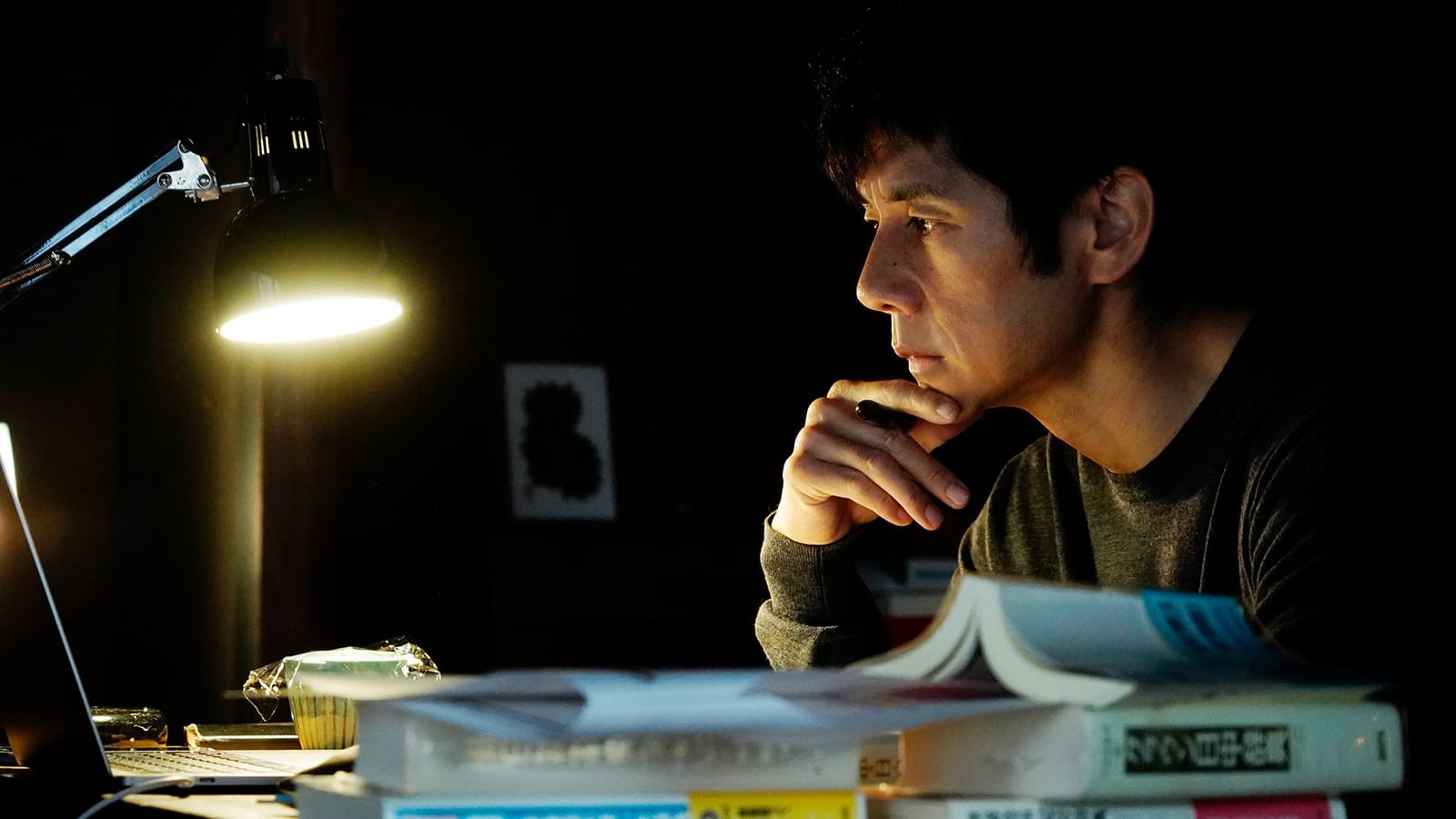

That assessment becomes true, although the textual rhythm is not easily transferred to life. Throughout the film, Yusuke’s grief unravels. Nishijima and Miura both play their characters reservedly, their straightforward deliveries hinting at numbness. Takatsuki is a key figure in dissolving the solidity of Yusuke’s state of grief, as he reveals his experiences with Oto and complicates the narrative Yusuke has formed. There is a captivating scene in the car when Takatsuki looks directly into the camera and details an ending of one of Oto’s stories that Yusuke has never heard. At the end of it, he essentially says, to know others, you have to know yourself. So far, Yusuke has assigned an impenetrability to his late wife’s mind, and Takatsuki challenges this notion, forcing him to look inward.

In scenes like this and in later ones with Misaki, who shares her own grief, the steady pace of the tape recording is broken. The interchanging languages and use of silence between characters and in the staging of the play, work to disrupt the predictability of communication and the assumptions people build. The unpredictability of real life is rendered through the specificity of language, which includes silence. Grief, especially, takes on a new shape when exposed to other people’s honesty. Hamaguchi’s less-is-more direction—with both the acting and his visual composition—reflects Yusuke’s faith in the text. He trusts the audience to find potency in the dialogue and extensive monologues and doesn’t insert vague symbolism or trite emotion.

While the film runs about three hours, its length is not a problem because Hamaguchi allows each moment to stand on its own without flashiness. The film is fluid and seamless, with a restrained score. The cinematography by Hidetoshi Shinomiya features rich contrasts in dark interiors, the dancing motion of sunlight, and glittering cityscapes. There is a particularly striking shot of Yusuke’s red Saab moving through planes of blue-white snow, followed by a scene of piercing sensitivity. Drive My Car works because of its very human approach to grief, neither rhapsodizing or deriding genuine pain and beauty. The film doesn’t settle for tidy resolutions; it doesn’t have to say everything because it simply bears witness.