It’s the early sixties and New York City’s booming art world is in full swing. A new generation of rock and roll artists are emerging out of dingy nightclubs and entering newfound record deals, some of whom are still finding their voices in the heart of Greenwich Village. New Wave cinema dominated the movie houses lining the city’s streets and the minds of impressionable dreamers, foreshadowing the coming tide of challengers who would defy artistic conventions. Warhol’s The Factory along with several other independent studios become common meeting places for celebrities and artists of all kinds, providing a cross-grounds for new forms of hybridity. Could there be another time or place that could have birthed a band as transgressive and iconoclastic as The Velvet Underground?

At least, that is what Todd Haynes’s new music documentary, eponymously titled The Velvet Underground, supposes. The film follows the band from their early music roots in childhood to their late career break, when the band ostensibly became the reigning curio of music’s coming New Wave. Its opening sequence captures the discomforting energy evident in both the music and the lives of The Velvet Underground, visualized through a montage of television clips, newsreels, and avant-garde short films played along with a discordant yet melodic guitar chord, as well as a more accessible rock track. For viewers who were unaware of the band (like myself), this is explosive. The visual tone and style are akin more to experimental films and helps Haynes’s film feel very irregular for the kind of conventional “rock doc” it teeters on the edge of becoming, at least from a narrative perspective. But as the film progresses, however, it becomes evident that this aesthetic is more than an ornamental surface, aptly personifying the band’s uniquely energetic sound.

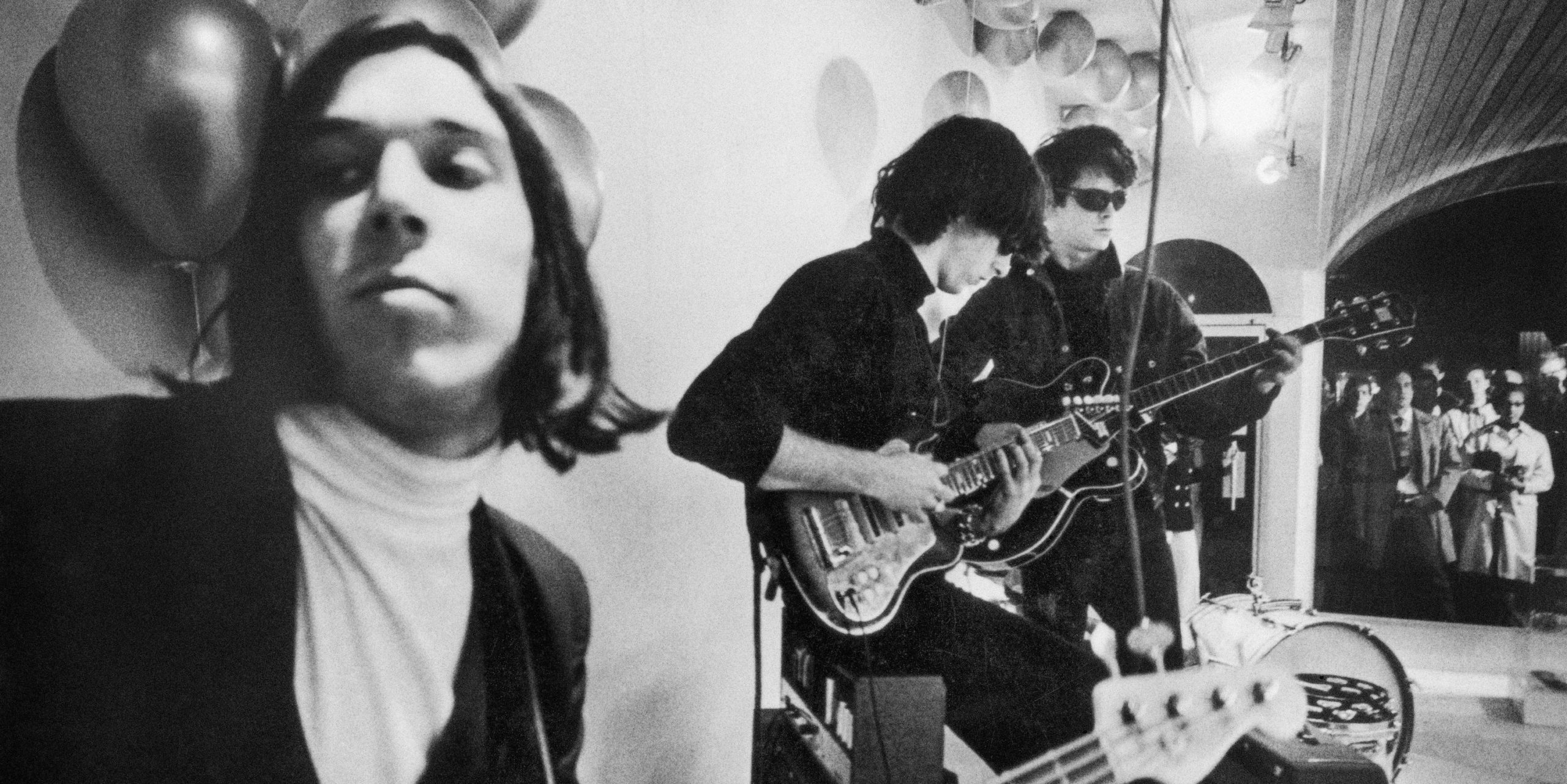

The core subjects of the film, the original four members of The Velvet Underground (Lou Reed, John Cale, Maureen “Moe” Tucker, and Sterling Morrison) and their surrounding figures, are portrayed primarily in their sixties and seventies period. The Velvet Underground generally follows the structure of most music biopics, beginning with a contextualization of the era, then delving into the musical and social adolescences of the band’s members (mostly Reed and Cale). We witness Reed, Cale, and Morrison experiment and develop their sound in early incarnations of the band, along with preliminary band member Angus MacLise. Eventually, MacLise is replaced by Tucker and The Velvet Underground is fully realized in 1965. Their uniquely nihilistic and droning music attracts the attention of pop artist and filmmaker Andy Warhol, who is hired as their manager. Warhol then pairs the band with model/singer Nico, vaguely suggested to be an unofficial band member, and produces their first album, The Velvet Underground and Nico.

The album has a middling commercial success, but it ultimately garners a cult following, launching the Velvet Underground into their “golden period.” However, tensions rise and the band members’ egos, along with Warhol’s dwindling management and their deteriorating mental and social lives, gives way to Cale’s departure and the end of the original Velvet Underground. The inclusion of a new member, Doug Yule, couldn’t save the band, and eventually the members parted ways, only to find recognition for their work decades later.

This may make the film sound like a strict biopic, but the focus shifts frequently between these personal history elements, the world building of sixties and seventies New York, and the placement of the Velvet Underground within the annals of music history. Haynes analyzes the film’s subjects more as an artistic movement than a group of people, primarily tracing the musical, literary, and artistic inspirations of the music. Reed’s adoration for pop rock and alienation literature from a young age, Cale’s collaborations with avant-garde artists like La Monte Young and John Cage during his burdening musical education, Tucker’s uniquely abbreviated style and penchant for standing up during performances, among other anecdotal images, depict the creation of a very abrasive and audacious sound unheard of at the time, a sound wholly identifiable and dependent on this specific group of musicians. Their songs reflected a social realism with themes of drug usage, depression, internalized shame, and sexuality conflicting with the pop rock sentiments espoused by the monoculture of the mid-twentieth century period. Certain details of the film, however, feel unnecessary despite their historical or social relevance. This is not an inherent flaw of Haynes’s film, but it does result in some meandering, even if the tangential material is still very fascinating and engrossing. Much of the threads surrounding the changing New York art world were interesting but were extraneous.

Though somewhat uninventive in its overall narrative arc, Haynes’s film is not devoid of character or personality. Various detours into the more personal and detailed experiences of the band members provide more insight into the perspectives and sentiments fueling their music. Lou Reed’s parents wanting to use an electric chair to “shock the gayness” out of him, for instance, is a perfect encapsulation of the alienation, shame, and discomforted marginalization he brought to The Velvet Underground. There is also comedic flair seeded throughout, built from the drug-fueled and youthful renegade antics of the era, Warhol having a nightclub audience handle overhead lights and frequently break them being a notable example of this.

The tone of each of these polarizing halves is bridged and supplemented by the soundtrack, which is at times melancholic and at others energetic. The best moments of The Velvet Underground are when Haynes opts to have the audience listen to the band’s music. The asymmetrical split screens and the wide cache of Warhol anti-films, Maya Deren, television clips, and performance recordings merge with songs like “Heroin” and “Sunday Morning” to create a uniquely lively yet trancelike experience. The interviews and narration tune out and the film becomes almost what a music video would be like if directed by Bruce Conner.

At times unfocused, Todd Haynes and his collaborators have created a uniquely transgressive visual and musical experience, though it is paired with an equally cliched and uninventive narrative. Nonetheless, The Velvet Underground is a very fitting tribute to the historic rock band.

The Velvet Underground is currently streaming on AppleTV+.