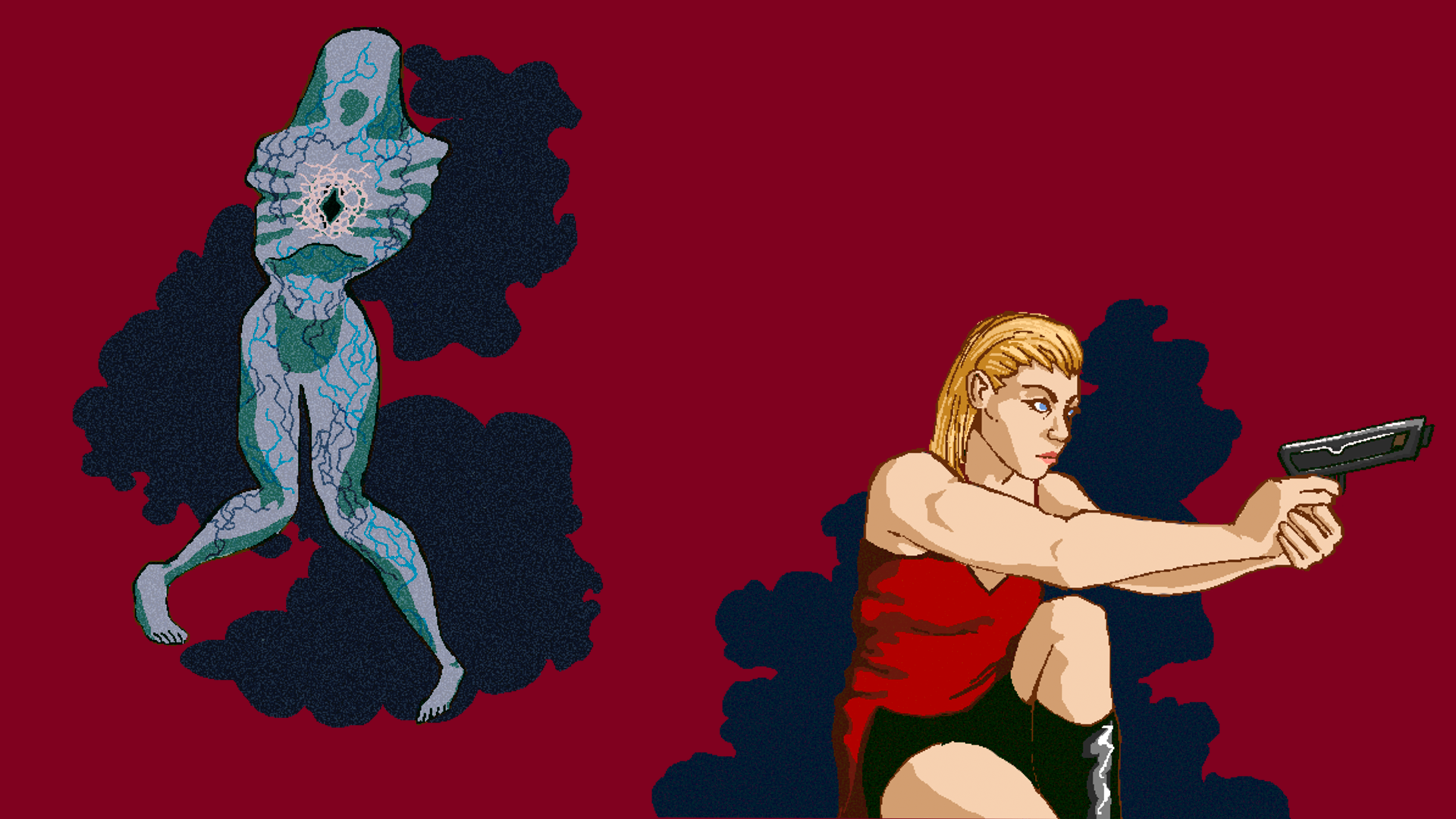

art by Elinor Bonifant

In the early 2000s, horror was in the midst of a transitional period. After Wes Craven’s 1996 meta-slasher Scream deconstructed and subverted the rules of the genre, filmmakers were forced to think of new ways to captivate and frighten audiences while also taking into account new technological advancements and the shifting aesthetic preferences of viewers. Simultaneously, the era’s ultra-sleek and high-tech blockbusters, like the Wachowski sisters’ 1999 sci-fi thriller The Matrix, raised the bar for filmmaking and changed what audiences expected. A far cry from the low budgets of twentieth century horror outings, horror films released between the years of 2000 and 2005 reportedly received an average budget of $36 million — which allowed for more elaborate worldbuilding, cutting-edge CGI technology, and the casting of higher-profile names. As a result, many turn-of-the-century horror films felt grander, glossier, and more cinematic than ever before. The aforementioned developments are reflected in Resident Evil, the 2002 action-horror film by Paul W.S. Anderson based on the video game franchise of the same name.

Anderson’s Resident Evil is representative of the time period in which it was released, using the prevailing aesthetics and technologies of the era to its advantage to set new trends and create an experience that felt at once current and forward-thinking. While somewhat dated now, Resident Evil still holds up as a well-crafted action-horror film, and its influence on the contemporary state of cinema is undeniable. Silent Hill, another horror video game adaptation of the aughts, also epitomized the landscape of horror at the time of its release; however, unlike Resident Evil, it failed to set trends, rather following them and coming across as derivative. This, in tandem with the public’s waning interest in big-budget horror, caused the film to be negatively received, but its position as one of the most faithful game-to-film adaptations has kept it at the center of conversations in the years since its release, leading to a recent critical reevaluation. Resident Evil and Silent Hill began on the same path and then eventually diverged from one another; now, albeit for contrasting reasons, they once again stand together as two of the most distinctly stylish and beloved 2000s horror films.

In 1996, Japanese game developer Capcom released the first installment in the Resident Evil video game series. The premise is simple: the Umbrella Corporation—a technological and pharmaceutical behemoth discretely conducting nefarious genetic research on the side—develops the powerfully mutagenic and highly contagious T-virus, which zombifies those who are infected. An outbreak occurs in the fictional town of Raccoon City, and Special Tactics and Rescue Service (S.T.A.R.S.) members Jill Valentine and Chris Redfield are sent to investigate. Resident Evil instantly became an international best-seller, prompting the development of numerous sequels and effectively kicking off the survival horror game genre.

With its straightforward yet highly engaging narrative, terrifying visual content, and schlocky B-horror sensibilities—not to mention its immense popularity—Resident Evil seemed perfectly poised for a successful crossover from console to cinema. In 1997, not even a full year after the release of the game, German production company Constantin Film bought the rights to a film adaptation, hiring Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers and Wrong Turn screenwriter Alan B. McElroy to write a script based on the first game. Capcom released Resident Evil 2 in 1998, and McElroy’s film was scrapped on the grounds that a film based on the first game would now be outdated. Genre legend George A. Romero, whose Night of the Living Dead series directly influenced Resident Evil, was personally asked by game director Shinji Mikami to helm the film adaptation after directing a live-action television commercial for Resident Evil 2. However, his script was also rejected; it was believed to be too gory for a mainstream theatrical release. The project went through a couple more writers and directors before eventually landing in the hands of Paul W. S. Anderson, who had already made a name for himself in the video game community with his 1995 film adaptation of classic fighting game Mortal Kombat. Anderson’s script initially began as a ripoff of Resident Evil entitled Undead, but the executives at Constantin Film loved it so much that, in 2000, they officially signed him onto the project as the writer and director. Undead was reworked into what would become the screenplay for the 2002 cinematic adaptation of Resident Evil.

Quite frankly, to call Anderson’s Resident Evil an adaptation of the original video game series in any capacity is a stretch. Anderson chose not to depict or even expand upon the lore of the games, instead building his own loosely inspired universe entirely from scratch. Although the general concept—a zombie outbreak in Raccoon City initiated by the Umbrella Corporation’s experimental and hazardous T-virus—remains the same, none of the beloved characters or storylines from the games are present, a decision that predictably angered devoted fans of the series who had been longing to see their favorite characters on the silver screen. Replacing Jill Valentine and Chris Redfield as the protagonist of Resident Evil was Anderson’s own original character Alice, portrayed by Milla Jovovich. Both literally and figuratively, Alice acts as a blank slate, beginning the film with amnesia and discovering what’s going on at the same time the audience does. Her actions determine how the narrative develops; she is required to unlock certain information and perform specific tasks before moving on to the next stage, much like a playable character in a video game.

Beyond the absence of integral characters and plotlines, Anderson’s Resident Evil dramatically diverges from the games in tone. Resident Evil 1 and 2, from which Anderson drew the most inspiration, contain plenty of combat and bloodshed, but they are horror games first and foremost. For the majority of the game, players wander through dark, menacing halls alone, evoking feelings of seclusion and despondency. There are doubts as to whether or not one will succeed in making it out alive, significantly amplifying the terror. The film, on the other hand, is an action-packed spectacle with multiple characters, most of whom are one-dimensional and insignificant to the progression of the narrative, fighting against zombies. There is a sense of camaraderie and relative safety in the film that the games do not have, and the action often takes precedence over the horror.

Resident Evil—while not as faithful to the games as it could have been, especially in comparison to how closely the Silent Hill adaptation would follow the source material—is fully capable of standing on its own as a well-made and thrilling action-horror film that very much serves as a time capsule of the unintentional kitschiness of early aughts cinema. Computer generated imagery is prominent throughout the film, and although it now looks archaic by today’s standards, it highlights the capabilities of the technology and is indicative of the era’s techno-utopian sensibilities. The noticeably slower frame rate at which the monsters’ animations are rendered in comparison to the rest of the film is endearing, evoking a sense of nostalgia for a time when this was something audiences had never seen before. The score—composed by Marco Beltrami in collaboration with industrial rock provocateur Marilyn Manson (because what turn-of-the-century horror movie would be complete without a soundtrack catering to the mall goths?)—is innovative and fittingly abrasive; it amplifies the intensity of the dire scenario, mirroring the relentless ambush by the undead with its pulsating synths and electric guitars. It is a product of the era’s predilection for futurism and consequently still sounds modern, influencing the intense and genre-defying sonic landscapes of contemporary action films. The opening sequence, specifically the grimace-inducing elevator decapitation scene, is chaotic perfection, recalling the Final Destination films. There are also some clever references to the game’s mechanics—such as corpses vanishing whenever the characters leave and reenter an area, or a character declaring that they only have three hours to complete their mission (which is how long players have to beat the Resident Evil games in order to unlock the bonuses). Fans of the franchise who may have been disappointed by the changes had something to look for and a reason to buy a ticket.

That being said, Anderson’s Resident Evil is not without its flaws. Although the film is, at its core, about a zombie apocalypse, the presence of actual zombies is minimal, and when they do appear, they often do so in hordes—another deviation from the source material, where they would individually assail the protagonist. Fortunately, the absence of zombies is compensated for through the inclusion of other monsters from the Resident Evil games. Prior to the twenty-first century, horror films relied almost exclusively on practical effects for creature design, but Resident Evil took a different route, instead employing computer generated imagery to give the film a more current, technologically adept look. There are some outdated practical effects on display here, but they look charmingly crude. The aforementioned shortcomings do not detract from the overall entertainment value of the film. Resident Evil remains a very solid action film with a seemingly unlimited reserve of energy.

Despite polarizing fans with its disregard for the game’s canon, Resident Evil was a bonafide hit, spawning five sequels and eventually going on to become the highest grossing film series based on a video game to date. The film arrived at a time when Hollywood was beginning to open up to the concept of a woman-led blockbuster, after years of Alien being the sole example. The early aughts designated a significant turning point in the ordinarily male-centric action genre, proving to Hollywood executives not only that there was a demand for female-led action films, but also that investing in such projects would be a highly lucrative endeavor. Resident Evil and similarly successful films like Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001) and Underworld (2003) arguably helped pave the way for the numerous women-led blockbusters that would dominate the 2010s: The Hunger Games (2012), Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Wonder Woman (2017), and so on. According to a 2018 study conducted by digital research agency Shift7 in partnership with the Creative Artists Agency, female-driven films generally performed better at the box office in comparison to male-driven films, and every film that grossed over $1 billion at the global box office between 2014 and 2017 passed the Bechdel test, meaning they included multiple female characters with agency independent of a male character. Resident Evil played a pivotal role in ushering in this era of increased inclusivity and female empowerment in cinema at the turn of the century.

As had become standard in Hollywood, studios rushed to replicate Resident Evil’s success, acquiring the film rights to other horror and horror-adjacent video game titles—including Doom, BloodRayne, and perhaps most notably, Silent Hill. It felt only natural that a Silent Hill film adaptation would follow in the advent of Resident Evil’s crossover to cinema. Not only were they the two definitive survival horror games of their era, but the first installment in the Silent Hill series, released by Japanese gaming conglomerate Konami in 1999, was also heavily influenced by Resident Evil. As a result, they had long been compared to one another, even though the differences between the two titles greatly outnumbered the similarities.

The original Silent Hill game follows protagonist Harry Mason as he searches for his missing daughter, Cheryl, in the eponymous town of Silent Hill. He soon discovers that the peculiar town in which he is now stranded is hiding a ghastly secret that he had inadvertently and inextricably involved himself in. A failed ritual from a few years prior had unleashed a dark, primordial force that feeds on an individual’s anguish and transforms the town into their worst nightmares, forcing them to confront the monstrous physical manifestations of their subconscious fears, guilts, and traumas. The town of Silent Hill exists in a plane entirely separate from reality and fluctuates between two alternate dimensions—the bleak, barren Fog World and the strange, hostile Otherworld—mirroring the sleep cycles. The Fog World represents non-REM sleep, and the Otherworld represents REM sleep, when an individual is more susceptible to nightmares. The shifts between the two realms are signified by an air-raid siren.

Unlike Resident Evil, which relied on B-movie violence and combat-based gameplay, Silent Hill focused on building an unnervingly eerie atmosphere inspired by arthouse horror films and psychological thrillers, specifically adopting elements from the surreal and visceral work of directors David Lynch and David Cronenberg. The protagonists of the Silent Hill games were not trained military personnel as in the Resident Evil games, but rather ordinary civilians with personal motives, and the storylines were dark and deliberately ambiguous, exploiting mankind’s innate fear of the unknown. With its more serious approach to the survival horror genre in comparison to its competitors, Silent Hill (and its subsequent sequels) garnered bountiful acclaim, with many people considering it the best survival horror game and one of the best video games overall. Consequently, the expectations for a film adaptation were very high.

Christophe Gans, a burgeoning French director known for his period horror film Brotherhood of the Wolf, was a huge fan of the Silent Hill games, and he was desperate to get his hands on the rights to a cinematic adaptation. Gans spent five years pleading with Konami, even going so far as to shoot scenes at his own expense to show his enthusiasm for the franchise, before he finally obtained the rights in 2004. His love for Silent Hill truly shines through in his 2006 film adaptation; he was committed to replicating the experience of the original 1999 video game as closely as he could. The film’s score consists entirely of rearrangements and remixes of composer Akira Yamaoka’s music from the first four games. Gans wanted to use Yamaoka’s original compositions, but he was contractually obliged to hire Canadian composer Jeff Danna, who had previously scored Resident Evil: Apocalypse (2004), the first sequel in the Resident Evil film series. Yamaoka was instead signed on to supervise Danna in the rearrangement process. The differences between Yamaoka’s work and Danna’s rearrangements are extremely subtle, and the score plays a key role in replicating the ominous and otherworldly atmosphere that had come to be associated with the Silent Hill games. The film’s visuals—including everything from the sparse, isolated Fog World to the rusty, decaying Otherworld—closely resemble the game as well. Furthermore, several scenes, such as the moment in which the protagonist first arrives in Silent Hill and experiences the Otherworld, are recreated almost shot-for-shot.

Silent Hill works exceptionally well as a video game adaptation, but perhaps only moderately well as a horror film. The town of Silent Hill—desolate, decrepit, and shrouded in foreboding fog and ashes—is unnerving; it is truly the ideal setting for a horror film. The creatures in the Silent Hill movie rely less heavily on computer generated imagery than the monsters in Resident Evil do; in fact, most of them are portrayed by dancers contorting their bodies in unusual ways, allowing for a more realistic and therefore more frightening look. Computer generated imagery is instead utilized in the death scenes and the transitions from the Fog World to the Otherworld. While more refined than the CGI featured in Resident Evil, it still does look fake at times, slightly diminishing the fear factor. Gans has since stated that this was intentionally done in an effort to evoke a sense of surreality. The film, clocking in at over two hours, admittedly lulls a bit, mainly during the scenes featuring Rose’s husband, Christopher Da Silva, portrayed by Sean Bean. Christopher’s subplot was thrown in at the last minute due to studio executives fearing the film, which had an almost exclusively female cast, would not fare well with the critics or the public (spoiler alert: it didn’t regardless). It is generally agreed upon by fans of the Silent Hill franchise that Christopher’s scenes were the weakest aspect of the film, detracting from the atmosphere and contributing virtually nothing to the plot. The central plot in itself is also quite convoluted. Fans understood it with ease as it was almost directly transposed from the game, but the average viewer left the theater bewildered with more questions than answers.

When Resident Evil was released, the horror genre was still struggling to find its footing in the new millennium, and this confusion is exemplified by the film’s aesthetics. Silent Hill, on the other hand, arrived at a time in which Hollywood horror had once again found its voice after an era of experimentation, and these developments are also reflected by the film. In the years that had passed between Resident Evil and Silent Hill, box office victories and cultural phenomenons like 2004’s Saw and 2005’s Hostel had revolutioned the genre and popularized the twisted, brutal subgenre known as “torture porn,” which pushed viewers to their limit with its gruesome depictions of carnage. In order to compete with these highly successful titles and pander to an audience that had grown accustomed to copious amounts of stomach-churning gore, Silent Hill had to increase the barbarity. As such, the film features some of the most graphic and genuinely repulsive imagery to ever be seen in a mainstream horror film. There’s a scene in which Pyramid Head—a towering, muscular, pyramid-headed humanoid monster wielding a massive spear—rips someone’s skin clean off. In another scene, a crowd watches in disgust as a woman’s face melts; the camera is unflinching as her charred flesh drips like candle wax. During the climax, another woman is split in half by barbed wire; her daughter rejoices as blood rains down upon her in a moment of disturbing catharsis. These sequences were so outrageously grisly that, after a certain point, they became ludicrous — acontrast from the shocking, macabre realism that made the torture porn outings of the era so effectively terrifying. They weren’t exactly frightening, but they made for some memorable set pieces.

Japanese horror—which experienced a surge in popularity in the early aughts due in large part to the success of Ringu (1998) and Ju-On: The Grudge (2002) as well as their American remakes The Ring (2002) and The Grudge (2004)—also influenced Gans’s Silent Hill adaptation. The story was slightly modified so as to capitalize on the vengeful ghost trope prevalent throughout J-horror. Alessa Gillepsie, one of the main characters from the game, was given a redesign for the film, and her new look bears a striking resemblance to that of the primary antagonists from The Ring and The Grudge.

Gans’s Silent Hill was unable to live up to its lofty ambitions, achieving only lukewarm success. Much of the film’s failure can be attributed to the fact that it simply arrived too late. The horror environment was already oversaturated with thematically similar films, and audiences unfamiliar with the games saw Silent Hill as a cheap imitation. Resident Evil, on the other hand, was able to thrive because it was an anomaly for its time. It predated the zombie movie renaissance of the mid-to-late 2000s and was one of the first women-driven blockbusters of the modern era; there was nothing it could adequately be compared to. By the time Silent Hill reached theaters, horror had also begun to return to its lower-budget roots; visually, it served as a reminder of a bygone era of unprecedentedly high production costs and uncharacteristically slick imagery in the genre and was no longer on-trend. As such, horror viewers, their tastes shifting once again, were uninterested in Silent Hill and eventually lost interest in the Resident Evil movies as well, which were becoming grander and higher-budget with each sequel. However, by growing increasingly reliant on the action components and neglecting the horror elements, the Resident Evil series was able to attract a new audience and continue to thrive. Action movies are characteristically high-budget and extravagant, and Resident Evil fit right in. Silent Hill did not have the same crossover appeal and therefore only appealed to a very niche audience. One mildly successful sequel—which was viewed by both fans and critics as a shameless cash grab—was released in 2012; then, the series effectively disintegrated.

Resident Evil and Silent Hill are special films. They are clumsy but sincere in their efforts to adapt their respective video game titles into films amidst the ever-evolving climate of horror, and they provide an unfiltered glimpse into the state of the genre in the 2000s—an era that for many people evokes a strong sense of nostalgia. The prevalence of video game adaptations diminished in the 2010s, but given the recent success of films like Detective Pikachu (2019) and Sonic the Hedgehog (2020), one can reasonably expect the 2020s to usher in the rebirth of the subgenre, which also means the revival of the now-defunct Resident Evil and Silent Hill titles. Director Johannes Roberts is in the process of rebooting Resident Evil. Currently slated for a 2021 release, the new entry in the Resident Evil cinematic universe is an origin story set in 1998 that Roberts promises is faithful to the games—unlike Anderson’s films, to which there will be no connections. It will be interesting to see how Roberts’s Resident Evil turns out. Will it be able to stand out in a climate directly influenced by the previous Resident Evil films? How will it reflect the aesthetic preferences of modern audiences and make use of recent technological advancements in filmmaking? Will the deliberate choice to pander to fans of the game alienate the general public, as was the case with Gans’s Silent Hill?

In a 2020 interview, Gans actually expressed interest in helming another Silent Hill film after temporarily relinquishing his duties for the 2012 sequel. The contemporary horror landscape, which is dominated by psychological thrillers and so-called “elevated horror,” feels primed for a new Silent Hill installment, but does it once again run the risk of coming off as derivative? Gans also implied that the potential sequel he is developing will be a spin-off of his original film and not a direct adaptation of any particular game in the series. How will fans feel about a new Silent Hill film marking a departure from the games? Nothing is yet set in stone, but one thing is for certain: neither film will be able to replicate the unparalleled magic and endearing strangeness of their 2000s predecessors.